Back to Silas S. Brown's home page

Heating a flat: vegetable-oil candles or oil-filled radiators?

Jump to: Candles | Electrical heatersCandles

Some people advocate using cheap paraffin "tealights" for heating electrical-only apartments when the cost of electricity is high. Besides the fact that this doesn't always `add up' (even if the tealights are good enough to give you 200 watt-hours each, you'll have to find a shop that charges less than your unit price of electricity per 5 tealights, but for lesser-quality ones call it 10---and if reaching that shop costs then you'd better factor this in), my main worry would be for safety---the American EPA noted significant pollution from paraffin candles (health risks + soot), not to mention the fire risks.Slightly more promising is the use of "floating water candles" made by suspending a wick in a simple plastic float on a body of water topped by cooking oil. This pollutes less (but see below), and it might `add up', but the cost of buying (or making) the wicks might be a bigger factor than you realised!

- Most cooking oils are about 33 MJ/L i.e. about 9 kWh/L, so divide the pence per litre by 9 to get the effective p/kWh of the oil (but allow for wastage). This has been known to halve the daytime rate of Economy 7 electricity---depends on prices in your region---but it will be increased by the price of the wicks (below).

- If you have any cooking oil that has gone out of date (or don't want to cook with for any other reason), you could also use this as a limited supply of free fuel.

- The flames are typically small---you may get only 25 to 30 watts per wick, so you will need "a few" for background heat. (That wattage figure is my guess, but it's consistent with manufacturers' claims that they last 10 hours on a 1cm-deep layer of oil: at 9 kWh/L that's 0.9 watts per square centimetre of the surface area that was required by each candle in their test setup, which I assume to be 30cm2 +/- 20%. Sometimes a larger flame can be obtained by not pushing the wick all the way into the float, leaving more of it aloft, but don't count on being able to do this consistently.)

- The price of wicks can be a significant extra. At that wattage, even if each wick

burns well for the full 10 hours, it gives barely 0.3kWh, so take the cost (in pence) of a pack of 50 wicks and divide it

by 15 to get the p/kWh cost of the wicks. At typical commercial

wick prices, adding this to the above cooking-oil cost might

in itself take this form of heating above your peak-rate electrical price

(unless you're using up wicks that have already been bought).

- In practice, you're less likely to get 10 hours per wick if you don't run this "heater" for continuous 10-hour sessions. When extinguishing and re-lighting later, it's difficult to re-use the same wicks, and doing so does not always result in a good flame (especially if they've already been used twice). Therefore, if heat is required in shorter sessions then you might need to double or triple the effective p/kWh from the wicks, due to early wick changes.

- You might consider just leaving the candles burning, which would make sense if the number of hours you want them "off" for, multiplied by the price of cooking oil per litre, divided by about 300, is less than the price of one wick. At 2015 UK prices, that worked out at 2 hours i.e. keep them burning if you're likely to want them again within 2 hours. This stratagem works only if the next required session is not likely long enough to require a wick change anyway given the length of time they've already been burning plus the interim, and at best it reduces the p/kWh back down toward the initial 10h/wick figure that might already be too high. Also, I wouldn't suggest leaving anything burning unattended even though it's safer than paraffin candles.

- Although the pollution from burning cooking oil is likely less than that from paraffin, it can't be nothing. The only data I could find was a Dutch literature review that said car tailpipe emissions are roughly similar between diesel and vegetable oil (which has since been shown to be one of the worst-polluting cooking oils: rapeseed and olive oil are significantly better although usually more expensive). Given diesel's 22%-higher MJ/L figure and assuming ~50mpg at 60mph, this means you'd need about 2000 wicks to match the pollution rate of a cruising diesel car (or 300 to 900 wicks to match it when idle, which, according to Tobacco Control's 2004 comparison, means 900 to 2700 wicks are needed to match the secondhand-smoke pollution rate of one cigarette). That assumes the vegetable-oil cars in the Dutch review weren't benefitting from emissions filters or catalytic converters (which, last time I checked, were not available for the floating candles): you might need to divide the above numbers of wicks by anything up to 50 if the catalytic converters were working at full efficiency on those oil-powered cars (which is unlikely). On the other hand, you might need to increase those wick-numbers if the oil-powered cars weren't burning fuel as completely as a wick does (which is entirely possible if they were just home-modified diesel cars). Anyway I hope the fumes from just a few wicks can be adequately handled by typical room ventillation if you don't get too close.

- In terms of total environmental costs, I couldn't find all the necessary figures to compare the pollution etc involved in producing and shipping a unit of cooking oil versus producing and transmitting an equivalent amount of energy across the UK National Grid at various times of day (both figures would vary with region), not to mention accounting for wicks and matches or other lighting equipment (think of the chemistry) versus any new electrical equipment that is required. My guess in 2015 was that neither would be a "clear winner".

Electrical heaters

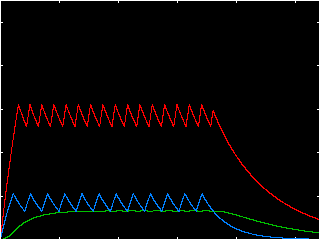

All electrical heaters convert 100% of their electricity into heat (one way or another), but how much of a difference does it make when and where that heat goes?![[This section has graphs but they are explained in the text]](oil1.png) In

, an oil-filled radiator uses heated oil (top line) to dampen the oscillation from the thermostat's hysteresis, resulting in a more stable room temperature (bottom line). To achieve the same minimum temperature with a cheap fan heater, the room temperature must oscillate more (middle line), which (with these numbers) increases consumption by 20%. The fan heater does bring the room to temperature more quickly (left); it also cools down more quickly after switch-off (right).

In

, an oil-filled radiator uses heated oil (top line) to dampen the oscillation from the thermostat's hysteresis, resulting in a more stable room temperature (bottom line). To achieve the same minimum temperature with a cheap fan heater, the room temperature must oscillate more (middle line), which (with these numbers) increases consumption by 20%. The fan heater does bring the room to temperature more quickly (left); it also cools down more quickly after switch-off (right).

If the room's insulation is improved so much that its total thermal conductance is halved, both heaters' consumption is roughly halved (the fan heater comes on for shorter periods and the radiator needs its internal temperature set lower), and interestingly the difference between them is also reduced (in this case the fan heater consumes only 10% more than the radiator, instead of 20%), although the radiator's consumption can be reduced a few more percentage points by using an element of lower wattage (while keeping the same size and internal temperature setting). This means (1) the benefits of dampening are more pronounced if you're not allowed decent insulation; (2) you should use the lowest wattage setting that reaches the internal temperature you need.

If the room's insulation is improved so much that its total thermal conductance is halved, both heaters' consumption is roughly halved (the fan heater comes on for shorter periods and the radiator needs its internal temperature set lower), and interestingly the difference between them is also reduced (in this case the fan heater consumes only 10% more than the radiator, instead of 20%), although the radiator's consumption can be reduced a few more percentage points by using an element of lower wattage (while keeping the same size and internal temperature setting). This means (1) the benefits of dampening are more pronounced if you're not allowed decent insulation; (2) you should use the lowest wattage setting that reaches the internal temperature you need.

It could take some experimenting to find, for a given outside temperature, which internal temperature corresponds to your preferred room temperature. The more expensive oil-filled radiators tend to have embedded software to help with this, and let you set room temperature in Celsius rather than providing an unmarked dial. Some models also advertise "patented" chimneys etc (I haven't yet found the patent numbers)---the effect of these is to increase heat transfer, so the fixed maximum internal temperature can sustain a higher room temperature for a given size of radiator, but I can't see how they'd improve the overall energy consumption associated with your desired room temperature (although users might appreciate the more-obvious column of warm air when feeling above it). The main energy-consumption advantage of these units is the Celsius user interface.

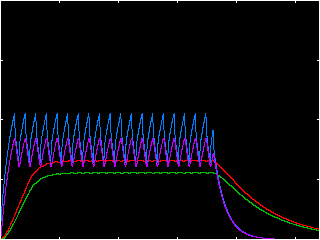

Going back to the badly-insulated room, when we very roughly simulate the propagation of heat from the area near the heater (top lines in each pair) to cooler areas further away (bottom lines in each pair), it can be shown that if occupants stay around the heater they can adjust it to reduce consumption by 15-20% in both cases; the coolness in other parts of the room is more sustained with the oil radiator than it is with the fan heater.

Going back to the badly-insulated room, when we very roughly simulate the propagation of heat from the area near the heater (top lines in each pair) to cooler areas further away (bottom lines in each pair), it can be shown that if occupants stay around the heater they can adjust it to reduce consumption by 15-20% in both cases; the coolness in other parts of the room is more sustained with the oil radiator than it is with the fan heater.

Specialist heaters like the "Dyson Hot" range claim to improve efficiency by clever air distribution; if good, that means it's "as if" you're staying near the heater even when you're not, so now we have a rough idea of what savings might be possible: 15-20%. I'd expect less in practice, and if an expensive model has a pay-off period of many years then it might break down first.

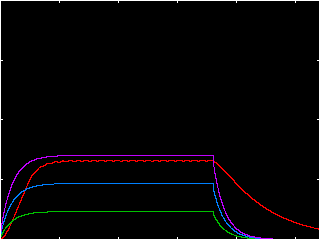

Low-wattage "always on" elements can consume less than oil-filled radiators on similar comfort settings, but the wattage must be matched to the desired temperature rise, as there is no thermostat to compensate for over-provisioning. The savings arise because, once the wastage of oscillating the room temperature above your desired minimum is removed, the main difference is in the radiator's residual heat after the final switch-off. In this simulation (top two lines) the radiator consumed 8% more during a 1-hour heating session, but obviously the longer the session the less difference it would make. (The bottom two lines show the effect of under-provisioning the always-on elements. It's hard to get right.)

Low-wattage "always on" elements can consume less than oil-filled radiators on similar comfort settings, but the wattage must be matched to the desired temperature rise, as there is no thermostat to compensate for over-provisioning. The savings arise because, once the wastage of oscillating the room temperature above your desired minimum is removed, the main difference is in the radiator's residual heat after the final switch-off. In this simulation (top two lines) the radiator consumed 8% more during a 1-hour heating session, but obviously the longer the session the less difference it would make. (The bottom two lines show the effect of under-provisioning the always-on elements. It's hard to get right.)

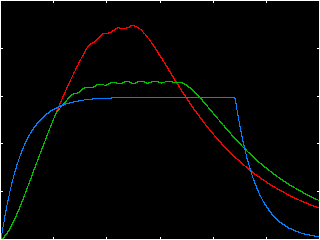

Conversely, if an oil-filled radiator is large enough, you might be tempted to deliberately set it too high, then switch it off at its peak and rely on its cool-down to keep the room above your desired minimum for a while. In this simulation, an oil-filled being set high then switched off is compared with an oil-filled set lower and run longer, and with a suitably-dimensioned always-on element run even longer, both with less than 5% savings in total consumption. This shows that, for a given total consumption level, you get shorter time above the desired minimum room temperature if you heat extra and rely on the cooldown. It might make sense if you're on Economy 7 or similar and plan to switch off just before the expensive tariff starts, but only to save the first 5 to 10 minutes of on-peak heating. In some circumstances that might be all the heating time you need, but to store hours of heat requires an actual storage heater.

Conversely, if an oil-filled radiator is large enough, you might be tempted to deliberately set it too high, then switch it off at its peak and rely on its cool-down to keep the room above your desired minimum for a while. In this simulation, an oil-filled being set high then switched off is compared with an oil-filled set lower and run longer, and with a suitably-dimensioned always-on element run even longer, both with less than 5% savings in total consumption. This shows that, for a given total consumption level, you get shorter time above the desired minimum room temperature if you heat extra and rely on the cooldown. It might make sense if you're on Economy 7 or similar and plan to switch off just before the expensive tariff starts, but only to save the first 5 to 10 minutes of on-peak heating. In some circumstances that might be all the heating time you need, but to store hours of heat requires an actual storage heater.

These notes are provided in the hope that they are useful, but they do not constitute medical, financial or safety advice. I certainly hope they are better than following dangerous suggestions on Internet videos though.

Copyright and Trademarks

All material © Silas S. Brown unless otherwise stated.Dyson is a trademark of Dyson Technology Ltd.

Any other trademarks I mentioned without realising are trademarks of their respective holders.